Blog Posts

Remembering Partition: Legacy of 1947 at LFA 2025

Chanan and the Goat

This account relates to my husband’s father, Chanan and his sister’s family by marriage. It’s a story of displacement and division caused by political expediency in which ordinary people were pawns to be manipulated. Or at least that’s my view – by Kathryn Kabra

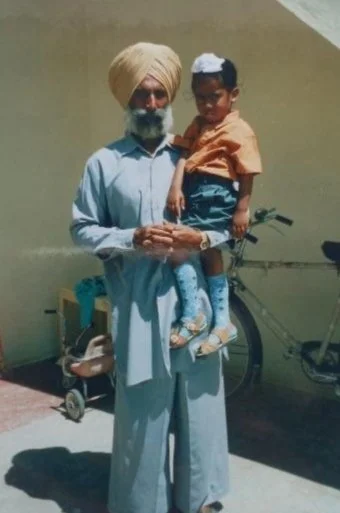

Chanan was born in 1926 in a village near Hoshiarpur. His family owned and farmed the land. He was the eldest of three brothers. He had little interest in taking over the farm, feeling there was a bigger world out there to be explored.

At some point in his late teens or early 20s, he met and became very friendly with a family of similar-minded people. When a government incentive scheme offering land in exchange for land clearance in Lahore came along, the family invited him to take up the offer with them.

They all moved to Lahore, worked hard to clear the land and establish a viable farm with every intention of settling there. Within a few years, Chanan realised this was not for him and returned to Hoshiarpur. This would be in about 1945. A few years later, he married and started a family; his firstborn was a daughter in 1949, my husband in 1951, and subsequently, three more children.

Meanwhile, in Lahore, the family were thriving; this was a family of 7 sons. The older ones work alongside their dad on the farm. Dharam, the youngest, was born in 1947. Sadly his mother died in childbirth.

Soon after, with Independence followed by partition on the horizon, it became increasingly dangerous to be a Moslem on the Indian side or a Sikh on the Pakistan side of the coming border. The family decided to make their way back to their old home, abandoning their new one with regret. Making this journey was perilous, and the surviving family members won’t talk much about it, but they do have one abiding happy memory. At the time of the journey, Dharam was a baby, so to feed him, they brought along one of their goats. The milk from this goat kept him alive throughout the journey. They all, including the goat, survived and yet again were involved in a land clearance settlement scheme, this time in an area abandoned by Moslem families fleeing India. Essentially the seven brothers eventually became the village, building separate homes and working together. This is the village we visit, and we have witnessed that the abandoned mosques have been preserved and respected over time.

When the goat eventually died of old age, it was buried with honour.

To wrap up the story, my husband’s eldest sister married the youngest son Dharam (who was kept alive by the goat). They are in their 70s now. One of Dharam’s elder brothers, who is still alive and still farming, gave us this account.

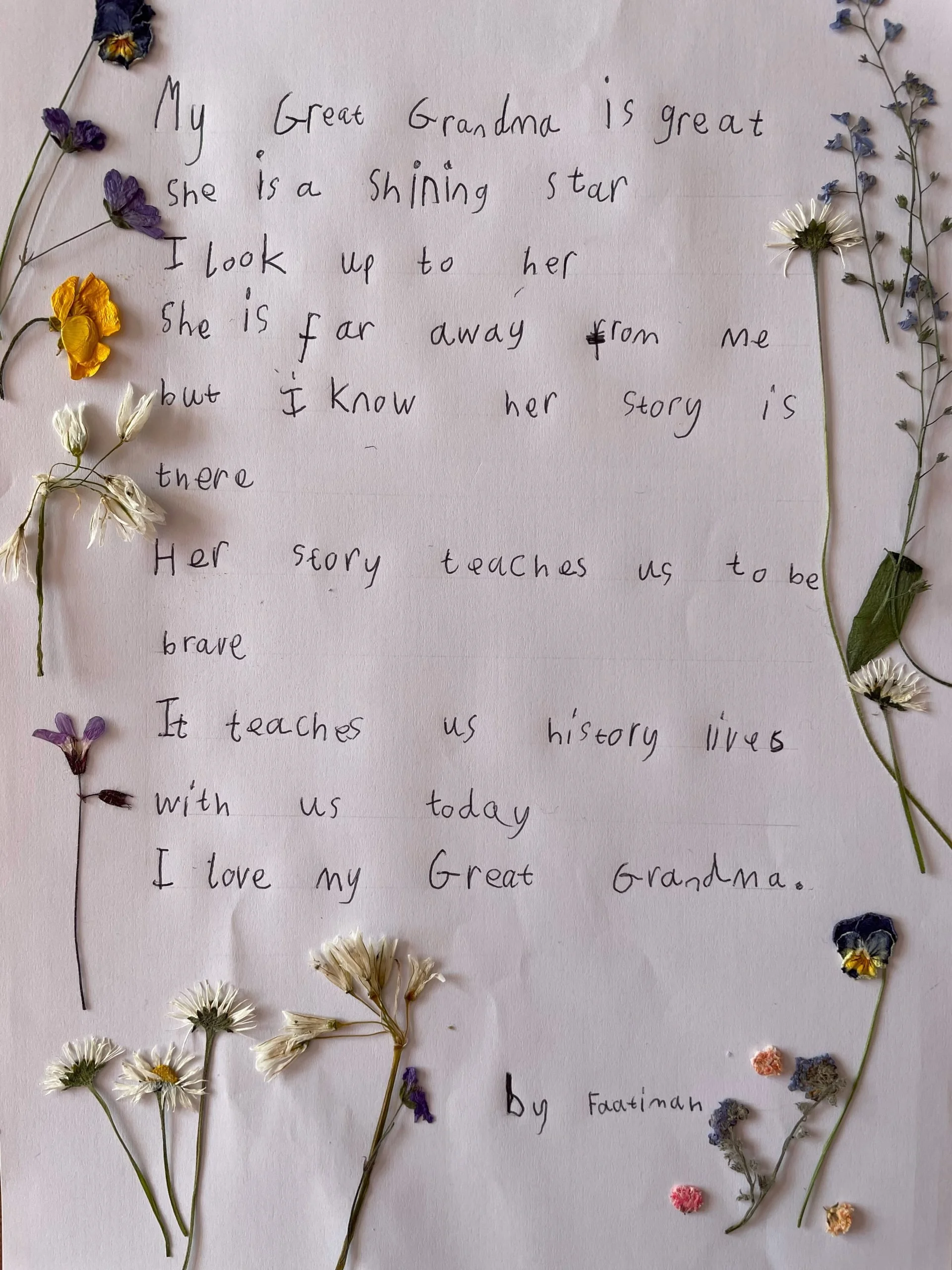

My Great-Grandma’s Partition Story

My great-grandma lived through Partition; her name was Mansur Faatimah Shah. I grew up listening to many stories of her endurance and bravery, about how she made her journey to Pakistan during the violence and disorder of Partition. She was born in pre-partition India. She lived in Kapoorthala village, Sheikpura Bohoi in the state of Riasat, current day India, with her family, the Kazi family, who earned their name due to their profession as judges during the Mughal empire. By the time my great-grandma was born, her family were agriculturalists. Their ancestral lands included a large portion gifted to them by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan for educating his children Dara and Aurangzeb. They lived a life of happiness.

She was married in 1945 to a man called Ali Ahmed Shah, who lived in Sultan Shah, which straddled India and modern-day Pakistan, an area in Punjab. One of my favourite stories of her youth is that her father borrowed an elephant from the raja at the time to ride during her wedding procession. In 1947 she was pregnant with her first child, and according to tradition at the time, she returned to her family home in Kapporthala village to see out her pregnancy there. In August, while she was still with her family in Kapporthala and five months pregnant, partition occurred, and violence broke out. Her father, due to his status in the village in dealing with local legal cases, was the target of a lot of anger, and therefore, as a Muslim in a now Hindu majority India that was in turmoil, was killed, as was his wife Hayat Bibi, my great grandma’s mother and her two sisters.

While we don’t know the whole story of how she was the only survivor in her immediate family, my grandfather’s family believe that her father’s friend, a Hindu man called Ram Ashra, took her to the train station. He also found a young boy called Fakir Hussain, my great grandma’s nephew, who we learn some of her story from, hiding in the fields of their wider village area. He also took Fakir Hussain to the train station, where my great-grandma was. They boarded a cargo train together. As my grandma was heavily pregnant, she needed assistance to board the train, a man named Ismail, who she often spoke about due to his kindness, bent down so she could use his back to leverage herself onto the train. They hid in empty coal boxes to avoid detection. The train, at one point, was intercepted by mobs, and many of the people on it were violently murdered. The police arrived before the violence reached my great-grandmother’s cabin, so she was spared.

Ram Ashra was tasked with the safekeeping of the family’s gold and jewels, which we know he buried in the ground, and which no one ever returned to recoup. When I think about it, this wealth was left in the blood-soaked mother land, which was ripped apart to give birth to a new country and all of its trauma. The land reminds me of my great-grandma and all the sadness she felt and saw as a pregnant woman herself. She was heavy with the promise of a new life and the burden and sorrow of the one that was violently taken from her.

The train eventually came to Lahore, and as they reached safety, they discovered other nieces and nephews of my great grandma and Fakir Hussain’s siblings. It is likely the children were given safe passage by someone to get to the train station. Fakir Hussain was reunited with four of his older sisters – Mahmooda, Nasir, Naseem and Zara, as well as his cousins Ishrar, Jaaji and Sajad. My great-grandma described the hunger she felt during her tumultuous journey, she was given a plate of roti, pickle ‘achar’ and cool water when she arrived at the station, and despite her upbringing of wealth and luxury, she described it as the best meal she’d ever had. What she discovered was her husband’s family had come to the train station every day in anticipation of her arrival. I can only imagine what a relief it was for all of them on the day she did finally arrive.

In the aftermath, she was traumatised by the horrific events that she witnessed and endured. When I spoke to my great Aunt, Zia Shah, my great-grandmother’s third daughter, she mentioned that her sisters’ children, who had also reached safety with her, provided some comfort and solace from what had unfolded.

They all settled in an area called Zafar Ke in Punjab. Eventually, the government repatriated a portion of their expansive lands within the newly formed Pakistan as recompense. In December, after this traumatic and life-shattering event where she lost everything she knew, she gave birth to a healthy young boy called Hassan Shah, my grandfather’s oldest brother. Her early life in Pakistan was spent on her husband’s ancestral lands in Sultan Shah. She moved to the city of Kasur, Punjab, along the Pakistani and Indian border, to ensure her children had the best possible education. This included her youngest son, my own paternal grandfather Khalid. Their home in Kasur was originally a converted stable that they owned. She went on to have six children, one of whom died in infancy, and two sons. She lived till she was in her eighties.

My paternal grandma Qouasar lived in London; her mother went to Pakistan in 1974 in search of her husband and was recommended a young law student, my grandfather, Khalid. They married in 1976 after my great-grandma met my grandmother Qousar. Her first question was whether my grandma could make butter. My grandma answered, regrettably, no. They went on to have four children, the third of which is my dad, Adnan. My grandma Qousar lived for some time in Pakistan after she got married, and she heard these stories of my great-grandma’s bravery. My grandma also told me that my great grandma was a herbalist; she had a great book with lots of natural medicines and remedies. One entry my grandma told me I thought was very interesting because it used shed snake skin, ground and mixed with makkan (butter). My great aunts would return home to my great grandma whenever they had a scar to apply some of this balm to speed up healing.

Growing up, these stories were valuable because they helped me to piece together my own story as a young British Pakistani Muslim. It is important to me to document and record this so her story is heard and not lost forever. As my grandma has dementia, the stories she tells me about her mother-in-law are losing detail and sequence. As the great Fakir Hussain also gets older, I worry I will never learn things about her life. I feel a responsibility to write these stories down, so the history of partition can be seen in the way my great grandma, the true hero of the story, experienced it, and not just through the eyes of the powerful decision makers – who didn’t face the consequences of their actions.

Khadijah

Memoirs of a young boy

Introduction

My name is Ishrat, Bano, Dilkusha Zuberi. Born, raised, and educated in the UK. I have always wondered how and why my destiny was intertwined with this green Island. My ancestors and parents were born in India but, overnight in 1947, became citizens of Pakistan. Their experiences of dislocation, trauma, perseverance, survival, and the trials of assimilation into a new society have left an indelible imprint on my identity. I have flitted in and out of an Eastern body and Western mind, oftentimes a hybrid of both.

As a Somatic Movement Educator and therapist integrating health and well-being modalities, embodied trauma has consistently presented. This has led me to train further in better understanding ancestral and collective trauma, known as ‘intergenerational or transgenerational trauma.’ The Partition of India, with the mass migration of its people, planted the seeds for intergenerational wounds. I believe that the South Asian diaspora living in the United Kingdom affected by Partition lives with the impact of long-term physical and mental health issues that have remained unspoken about: ‘In important ways, an experience does not really exist until it can be named and placed into larger categories’ Bessel Van Der Kolk (Research Professor in the area of trauma).

Thomas Hubl (Renowned trauma facilitator and author) states a ‘collective trauma necessitates a collective response.’ This article serves as my small contribution to creating such a response. Hubl further expands, ‘No matter how private or personal, trauma cannot belong solely to a family, or even to that family’s intricate ancestral tree. The consequences of trauma seep across communities, regions, lands, and nations’

I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to Sadiya and Irfan Ahmed for guiding and training me in conducting oral histories for archival purposes. This story may not have been shared without their vision and dedication to establishing Everyday Muslim. This narrative represents my first written work on this subject matter. It is about a young boy, Ghulam Haider, who witnessed a harrowing scene of one particular train that pulled into a platform at Lahore Railway Station arriving from India during the Partition year.

Brief Background

In 1990 my mother – Nighat Jehan Khan, and Ghulam Haider were introduced to each other and married. I had the honour and blessing to become the stepdaughter of Ghulam Haider.

This narrative recounts a brief moment in the life of Ghulam Haider, but one that remained in the deep chambers of his mind and body for decades, silent and dormant, voiceless and hidden (unspoken and suppressed). It has been carefully unearthed like a newly discovered ancient excavation site. The rubble surrounding the ruins was sensitively and delicately cleared, revealing what had been frozen.

I have strived to gather details for this biographical composition to the best of my ability and, importantly, to honour and not forget all those souls whose journey on that fated day was incomplete. Considering the constraints presented by Ghulam Haider’s age of ninety, his fragile health and the emotionally taxing nature of the occurrence, I conducted several sessions with him spanning two years. Sadiya and Irfan also interviewed him in February 2023. This work synthesises the recordings, transcripts and notes from all these sessions.

Who is Ghulam Haider?

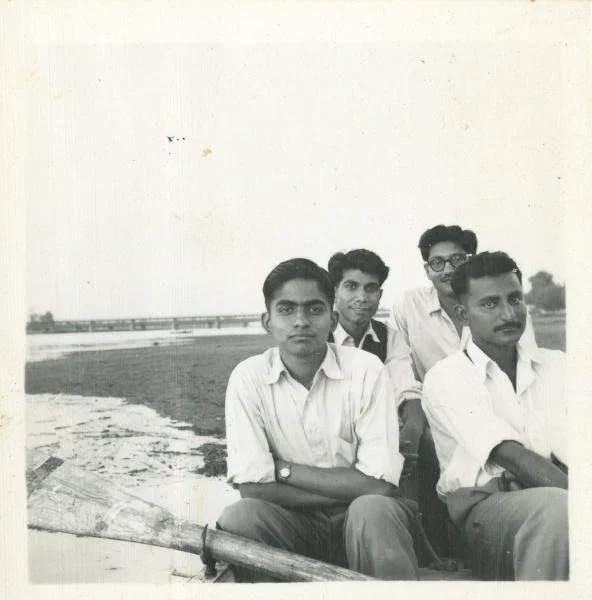

Ghulam Haider is a distinguished and respected retired Civil Engineer. After completing his first degree from Lahore, he earned his MSc from Imperial College, London. Born on June 11th 1933, in Lahore, British India, Ghulam Haider attended Central Model School. His stability and security were short-lived when his father passed in 1945. With the increasing unrest and violence in Lahore, the family moved to Gujranwala, 42 miles from Lahore. Here, life was tuff with financial struggles and illness, instability and adjusting to life, missing his friends and teachers in Lahore.

Ghulam Haider possesses a rare set of values and traits that are hard to find today. He never considers any task an obstacle and doesn’t complain about it being burdensome or tiring. He exudes the qualities of a responsible and affectionate father, placing his hand on my head with a smile filled with love and blessings. I have written this article for my beloved stepfather, who has been a constant and caring presence in my life; this article is his voice, expressing the trauma held within him for decades. It aims for Ghulam Haider to be heard and witnessed and for the Muhajireen (immigrants) to be honoured and remembered.

The Incident at Lahore Station

During his boyhood, Ghulam Haider engaged in extracurricular activities, including drama and debating, and was an active and dedicated Scout member. As part of their training, the young Scouts partook in voluntary work. This came by way of providing much-needed water to the parched and exhausted passengers crossing the new border into Pakistan and arriving at Lahore Railway Station.

Ghulam Haider remembers how the Coolie’s, the station luggage staff, would daily transport barrel-like containers of water on a wheeled carrier and carefully align them with the doors of the carriages of the oncoming train. Each barrel had a tap feature, ensuring the Scouts had easy access to water for refilling their jugs. One Coolie would stand near each carriage, poised to open the doors once the train settled safely along the platform.

As Ghulam Haider proudly stood tall, eager to help alleviate the thirst and discomfort of the travellers, he heard the Scoutmaster direct the Scouts to hold their metal jug filled with water along with a metal tumbler and be prepared to give water to the travellers quickly. Their journey was gruelling in the cramped trains. The relentless heat from the bright, hot sun glared its beam over everyone. ‘We moved nearer the doors following the Scoutmaster’s instructions, and as the train stopped, we adjusted our bodies to face the door of the carriages’, Ghulam Haider recalls.

As he connects to the memory of this horrific event, his gaze is distant and lost, eyes glazed with a bottleneck of tears. His head droops towards his chest as his body tenses, almost frozen. His emotions are high yet still bound to that young boy, unable to comprehend and metabolise what he witnessed even now in his nineties. Despite its vivid presence, he struggles to articulate the scene. The young boy does not have the vocabulary to express what he saw, a profound testament that the trauma still exists in his soma/body.

As I read my notes on Ghulam Haider’s recollection of this event, I was struck by how different it was from the world we live in today. Back then, children spent their days playing outside with one another, free from the distractions and dangers of screens and devices. They didn’t have access to the violent films and media that are so often a part of our daily lives. I am at a loss to imagine what it must have been like for a young, innocent boy like Ghulam Haider, who had never been exposed to such things, to suddenly find himself confronted with scenes of brutality and horror. I can only imagine how deeply it affected him and how much it dysregulated his sense of safety and security. My mind-body freezes as I cannot process the gruesome scenes he describes below.

Ghulam Haider was familiar with the task on that day as he had carried it out multiple times before, but this time there was a noticeable difference; the usual cacophony of noise was conspicuously absent. No people were on top of the train, no cheers of excitement or shouts of “Allahu Akbar” and ‘hum agaya, hum agaya’ (we’re here, we’re here!), joyously announcing their arrival at their destination. On previous occasions, the train would be packed with passengers on the roof and leaning out of the windows, but it was eerily quiet on this day. As the train approached the platform, it did so with an unnerving slowness; he recalls feeling confused and frightened, unsure of what was about to happen. He remembers feeling terrified, as did all the Scouts. The air was thick and suffocating, yet the sound of the chugging train offered a strange focus for all, but the young boy had no idea what was to come. He cannot recall what the driver and guard were doing.

(PLEASE NOTE: THE FOLLOWING PARAGRAPH INCLUDES A VERY GRAPHIC ACCOUNT OF A MASSACRE)

TO AVOID READING SKIP TO ‘CONCLUDING THOUGHTS’

THE SCENE INSIDE THE TRAIN – CAUTION, GRAPHIC DETAILS

As the train came to stillness, a Coolie allocated at each carriage opened the doors, and streams of blood poured out. Ghulam Haider and the other Scouts entered the carriages with their jug and glass. His first sight was of dead bodies strewn and piled on the seats and carriage floor. Only women, babies and children were on the train. Some women had their legs spread apart, daggers pierced inside their vaginas. Young girls had their breasts cut off, and one scene that Ghulam Haider cannot erase was that of a mother breastfeeding her baby, both mother and baby stabbed in that very moment. Young girls, elderly women, babies’ throats slit – all dead. There were no men on the train except for the train driver. It is believed they were forced out of the train and taken elsewhere, where they were killed.

Shocked into a freeze and overwhelm, Ghulam Haider could not utter a word, totally traumatised and unable to flinch, paralysed with horror; he had no sense of linear time and could not recall how long he was in that state inside the carriage. At some point, he heard the Scoutmaster frantically shout, ‘Bahar niklo, bahar niklo (come out, come out)

The boys eventually exited the train and converged in one location. Stunned, speechless, no boy uttered a word, totally traumatised. When Ghulam Haider eventually returned home, he told his family everything; they all broke down in tears and condemned the murderers. He had trouble sleeping that night and for many nights afterwards, tossing and turning as the memories played in his head; this is what is today known as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); he has no recollection of what happened the following day.

Concluding Thoughts

The cycle continues: India is perhaps playing out the role of a coloniser of another minority living on its soil; Pakistan is a broken, bleeding limb. Little has changed since Partition: chaos and uncertainty still prevail. The two nations continue to suffer colonialism’s residual effects and collateral damage. Ghulam Haider has written further about his thoughts in a book, ‘The Road Less Traversed.’

As I complete this narrative, I would like to share this quote:

‘The past has not passed. The dust of karmic events creates a great rippling wake whose waters retreat only to push out ahead and descend again. In this way, a collective event’s residual and undigested energy, like the (Partition) and Holocaust, can become a great tsunami.’ –

Thomas Hubl – Healing Collective Trauma.

In memory of each soul who died in this horrific way. May you all be in eternal peace in grace and love.

Author Ishrat Zuberi